REPORTS

2018 Skin Tumors in Children

Presented by: Jane M. Grant-Kels, MD, FAADFounding Chair Emeritus, Derm Dept, UCONN. Vice President Chair to Dept of Dermatology. Professor of Dermatology, Pathology and Pediatrics. Director of Cutaneous Oncology Ctr and & Melanoma Program. University of Connecticut Health Center, Farmington, CT, USA

Skin tumors in children are different than those found in adults, leading to adjustments in work up and diagnostic approaches. Specifically, the epidemiology and pathogenesis are distinct and many times an underlying genetic condition in children or other diseases are the reason for modification. In fact, skin tumors can occur in the context of hereditary genodermatoses with cancer predisposition, such as basal cell nevus syndrome, xeroderma pigmentosum, epidermolysis bullosa, or oculocutaneous albinism.

The three main skin tumors to be aware of include:

- melanoma,

- basal cell carcinoma (BCC),

- and squamous cell carcinoma (SCC).

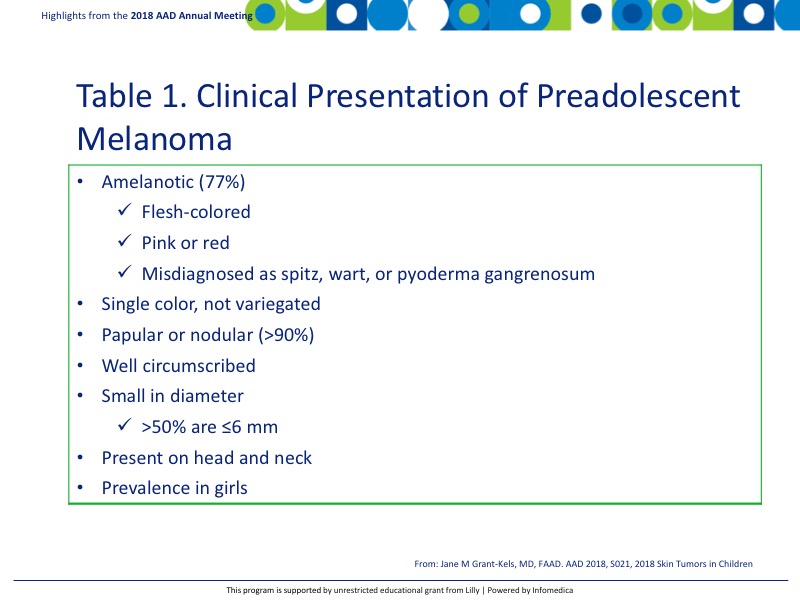

There are two types of melanoma found in children; preadolescent melanoma (<11 years) and adolescent melanoma (11-19 years), either of which may manifest in the second decade of life. There is a misconception among pediatricians that melanoma does not occur in children. Although it is rare, the incidence of melanoma is rising yearly in this population.1 While the adolescent melanoma is very similar in behavior and treatment as adult melanoma, preadolescent melanoma is a distinct disease.1,2 The traditional ABCDE standard grading system is not effective in the preadolescent population as the manifestations of the disease are different. Preadolescent melanoma presentation can include the features reported in Table 1.3

Based on these differences in preadolescent melanoma, the ABCDE standard grading system has been modified to greater detect melanoma in preadolescent patients.

- A = Amelanotic

- B = Bleeding

- B = Bumps

- C = Uniform Color

- D = Small Diameter

- D = De novo development

- E = Evolution

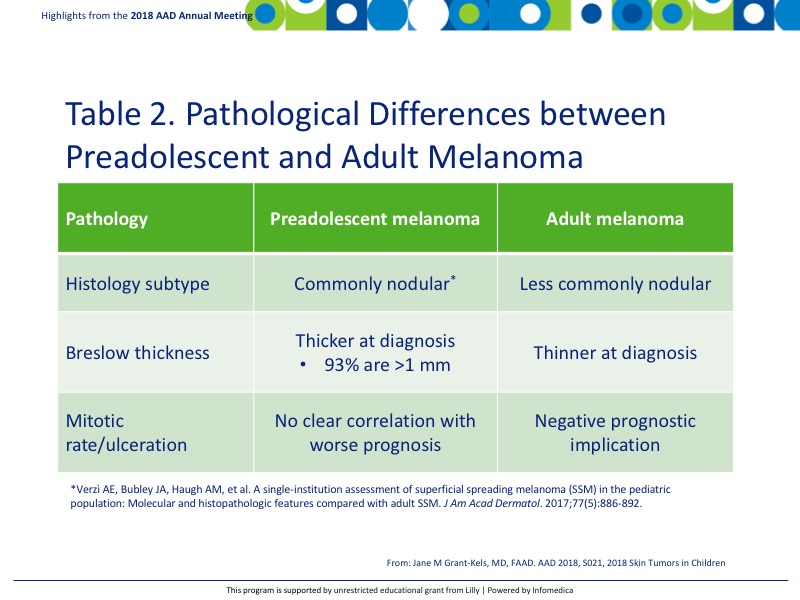

The diagnosis between adult and preadolescent melanoma also shows pathologic variations, further suggesting that preadolescent melanoma is its own disease (Table 24). To date, there is no AJCC TNM staging system for children and thus the adult system is used for determining staging. It is important to note that children should not undergo sentinel lymph node biopsy for staging, because results are likely to be positive even in benign melanocytic lesions.

There is a paucity of clinical studies focusing on the proper management of preadolescent melanoma and thus treatment frequently follows adult guidelines. Radiation is infrequently used, and treatments focus primarily on surgical excision, targeted and biologic therapies.

BCC is the next most frequent type of cancer in children after melanoma. The frequency of de novo development is exceedingly rare with ~100 cases reported worldwide in the literature.5 A genetic disorder or other condition is almost always associated with BCC development, although exposure to sunlight plays a role. Patients with a history of heart/lung transplantation or history of radiation therapy are also at an increased risk for BCC development. Patients with a history of radiotherapy often have latency in BCC development with manifestations occurring in their 20s. Exposure to carcinogens increases the development of BCC as well.

BCC most commonly diagnosed as a nodular form but may present as morpheaform and superficial BCC. It frequently occurs in areas exposed to sunlight, with 90% of de novo pediatric BCC presenting on the face. The most common treatment is excision, with or without using the Mohs technique. However, nearly 20% developed recurrent tumors during a follow-up period ranging from 4 months to 20 years. Truncal and ear/nose development are also possible and suggest a higher lifetime risk or higher rate of recurrence, respectively. BCC metastasis to the liver, lung, and bone has been reported in the literature.5

Similar to preadolescent melanoma, there are no recommended guidelines for children.

The use of radiotherapy is traditionally avoided due to lifetime risk of subsequent malignancies. Photodynamic therapy is an option in patients with basal cell nevus syndrome, as well as treatment with hedgehog pathway inhibitors for locally advanced or metastatic BCC. There is a lack of well controlled studies for hedgehog pathway inhibitors in pediatric population.

SCC is the least common of all pediatric cancers with only 6 cases documented in 28 years.6 There is no predilection in gender, but SCC does appear more frequently in children with darker skin. A history of transplant related immunosuppression, radiotherapy, burned/scarred skin, and infection with human papilloma virus have also contributed to SCC development. Cumulative ultraviolet light and the severity exposure plays a role in development of SCC in children as does in adults.

Clinical presentation of SCC is similar too in adults. The first step in diagnosis is to rule out any underlying condition and histological conformation of the diagnosis Patients must be treated aggressively especially if they have concomitant epidermolysis bullosa and always sunscreens should be strongly recommended.

Key Messages

- In children who present with skin tumors, look for underlying genetic or medical conditions.

- The prognosis for children varies from that of adults.

- Clinical presentation of skin tumors may vary from presentations commonly seen in adults.

REFERENCES

Present disclosure: The presenter has reported that no relationships exist relevant to the contents of this presentation.

Written by: Debbie Anderson, PhD

Reviewed by: Victor Desmond Mandel, MD