REPORTS

Atopic Dermatitis: New Developments

Presented by: Lawrence F. Eichenfield, MD, FAAD Professor of Dermatology and Pediatrics. University of California, San Diego. Rady Children’s Hospital, San Diego, CA, USAIt has been 30 years since the discovery of increased phosphodiesterase-4 (PDE-4) activity and decreased intracellular cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) levels in peripheral blood leukocytes of patients with atopic dermatitis (AD).1,2 This knowledge led to the development of targeted therapy for PDE-4 in the treatment of AD as an anti-inflammatory therapy. Long-term studies are now available for PDE-4 inhibitors, such as topical crisaborole.3 Study AD-301 and AD-302 were both double-blind, vehicle-controlled, safety and efficacy studies that lasted for 4 weeks.3 The corresponding long-term study was AD-303, which was an open-label, single-arm safety study that lasted for 48 weeks.4

In the initial study, patients were randomized to receive either crisaborole or vehicle BID for 28 days. After completion, patients were enrolled in the long-term trial where all patients received crisaborole BID and were reevaluated every 28 days. Crisaborole demonstrated statistically significant ISGA score of clear or almost clear compared to placebo (P<0.001) with significance seen as early as day 8.3 Long-term safety data demonstrated a low frequency of treatment-related adverse events (TRAEs), no adverse events (AEs) differences over time, no accumulation issues, and no safety signals in vitals, laboratory values, infections, or neoplasms.4 Certain information is still unknown about crisaborole such as:

- Comparative efficacy

- Cost-efficiency

- Effect on regions (face)

- Issues with stinging

- Data for patients under 2 years of age.

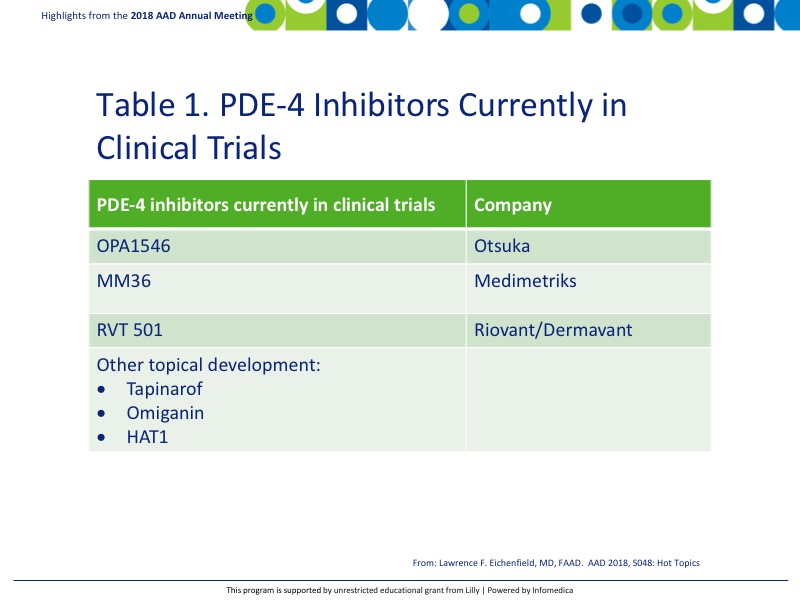

There are additional PDE-4 inhibitors currently in clinical trials including, but not limited to, the following reported in Table 1.

Initial investigations of tapinarof (GSK2894512) cream in patients with moderate-to-severe AD have shown promising results in various dose levels. TEAEs were reported in 13% to 15% of patients in the treatment groups compared with 10% in the vehicle groups. Minimal AE data was reported for this study.5

A phase 2 study of a topical JAK inhibitor, JTE-052, has also been studied and showed similar responses to change in modified Eczema Area and Severity Index (m-EASI) score from baseline as tacrolimus, an active control. The study also demonstrated a much lower rate of application site reactions than found in tacrolimus.6

The prostaglandin/leukotriene pathway is another avenue that is being researched. The arachidonic acid pathway is responsible for transforming plasma membrane phospholipids into eicosanoids, a class of inflammatory mediators. While leukotrienes are important in asthma pathogenesis, eicosanoids have been found to be in high concentrations in the skin of AD patients.

ZPL-521, a cytosolic phospholipase A2 (cPLA2) inhibitor, prevents the conversion of plasma membrane phospholipids to arachidonic acid, which is the rate-limiting enzyme in eicosanoid production.7

The prevention of AD should also be strongly considered in high-risk infants. Use of emollients has been shown to decrease the incidence of AD development in children 6 months of age [relative risk (RR) 0.50, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.28-0.90] (P=0.02).8 Therefore, it was suggested that emollient therapy from birth represents a feasible, safe, and effective approach for atopic dermatitis prevention.

Dupilumab is a potent blocker of IL4/IL13 (Th2) pathways and has been approved for use in AD at a loading dose of 600 mg with 300 mg every other week subsequent dosing. Data from the CHRONOS study demonstrated a significant improvement in the Investigator's Global Assessment (IGA) score, Eczema Area and Severity Index (EASI) 75, and EASI 90 scores with dupilumab compared to placebo over a 52-week period.9 Non-responders were also reviewed, and while they did not reach EASI 75 endpoint, patients still demonstrated good, very good, or excellent responses on the IGA score.

A study to assess the long-term safety of dupilumab administered in pediatric participants (≥6 months to <18 years of age) with atopic dermatitis is still going.10 This phase 2a, open-label, ascending-dose study for AD patients failing topical corticosteroids investigated the use of dupilumab in ages 6-11 and 12-17 years.10 IGA scores for each group were 4 and 3 or 4, respectively. Two dose levels were used in each age group: 2 mg/kg and 4 mg/kg. This was a 2-part study with part A having 1 dose with an 8-week follow-up and part 2 with 4 weekly doses with an 8-week follow-up. Initial pharmacokinetic studies showed favorable results with both parts of the study in both groups of children with no unusual accumulation.

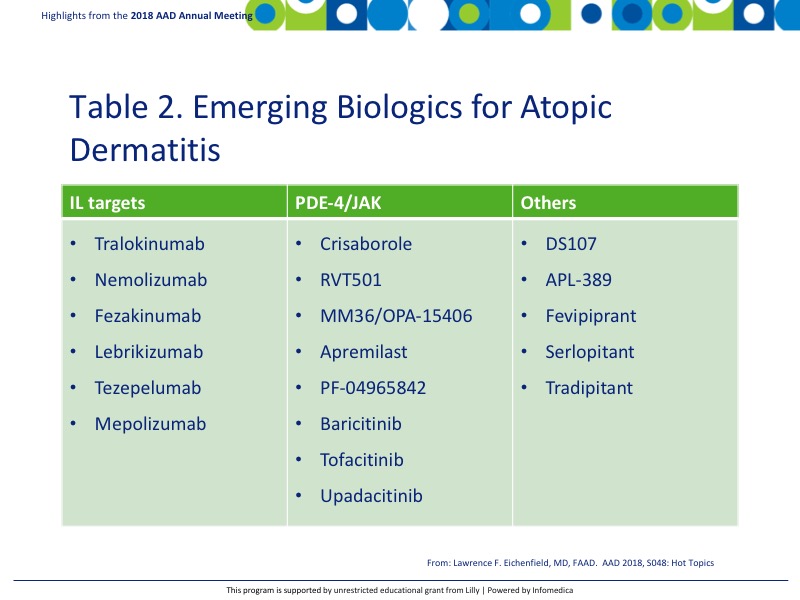

JAK inhibitors, such as baracitinib, upadacitinib, PF-04965842, and ASN002 have also been showing promise in adults with moderate to severe AD.

There is an upstream of emerging biologics for use in AD, many of which are still in clinical trials (Table 2). The area is expected to continue to grow with new treatments becoming available for AD patients in the coming years.

The use of systemic therapies, especially biologics, for AD should be carefully considered before initiated. Current recommendations from the International Eczema Council should be consulted to determine the best time and approach for incorporating systemic AD therapy.

There is an avenue of research that is focusing on the microbiome approach to treat AD. Preliminary research has shown the presence of a Staphylococcus coagulase negative bacteria on the skin that secretes lantibiotics which are antimicrobial to Staphylococcus aureus.11 Research in this area is ongoing with a great interest in results.

Key messages

- Long-term safety data of PDE-4 inhibitors (crisaborole specifically) show promising results with limited safety concerns.

- Additional PDE-4 inhibitors are currently in clinical trials.

- The prostaglandin/leukotriene pathway is being investigated as it was shown that patients with AD have a higher level of eicosanoids in the skin. ZPL-521 is currently under investigation as a possible treatment approach.

- Dupilumab and JAK inhibitors are gaining ground in the biologic armamentarium for the treatment of AD. Dupilumab has shown favorable responses and is currently being researched in children and adolescents. There are numerous other biologic drugs currently under development.

- The microbiome of patients with AD has been shown to be different. Research is focusing on Staphylococcus coagulase negative species as a possible approach to treatment.

REFERENCES

Present disclosure: The presenter has reported that he is a consultant or investigator for Anacor/Pfizer, Cutanea, Dermavant, Genentech, Galderma Laboratories, Leo, Lilly, Matrisys, Medimedtriks, Morphosys, Novan, Novartis, Otsuka, Regeneron/Sanofi, and Ortho Dermatology.

Written by: Debbie Anderson, PhD

Reviewed by: Victor Desmond Mandel, MD